At the beginning of what became known as the Reformation,

books and the way information was shared became especially important. A major

innovation during this time was the invention of the movable type printing

press. To us, that might not seem like a big deal, but it completely changed

how information was spread. A helpful comparison is the way copy machines and

the internet allowed people to create and share content without needing

permission from a central authority. Just like social media helped spread ideas

during events like the revolution in Egypt, printing allowed people in the 15th

and 16th centuries to share new ideas more freely.

Johannes Gutenberg is usually credited with inventing the

movable type printing press in the 1450s, though others were working on similar

ideas around the same time. Movable type was actually invented earlier in

China, but it wasn’t widely adopted there—possibly due to the complexity of the

Chinese writing system, which includes thousands of characters.

Gutenberg’s key insight was that instead of carving a full

page of text, you could make small, reusable letter blocks. These could be

arranged to form words and lines, then reset and

After printing maybe 50 or 100 copies of a page, the printer could reuse all the letters again for a new page. This made printing way faster and much cheaper—cutting costs by about 95%. It was such a change that even the idea of children’s alphabet blocks comes from the way these letters were stored and used during printing.

He also made a new translation of the Bible by going back to

the original Hebrew, Greek, and Latin sources. That made his version of the

Bible more accurate and readable for scholars of the time. Once people started

reading it for themselves, they began to question the church’s teachings and

how information had been controlled.

Most students are taught that the church didn’t allow regular

people to read the Bible. While that’s partly true, it wasn’t just about

control. Books, even printed ones, were expensive, and not everyone was

literate. Still, Erasmus's ideas encouraged people to read for themselves and

ask questions.

His work had a big impact on Martin Luther. Luther was born

to a peasant family, though his father was fairly wealthy and wanted Martin to

move up in the world. He sent Luther to study law. One day, while traveling

home across a field, Luther got caught in a thunderstorm. A lightning strike

hit nearby, and he panicked. He dove into the mud and made a vow to God that if

he survived, he would dedicate his life to God and become a monk.

When he made it home safely, he remembered the promise and followed through, even though his father wasn’t happy about it. As a monk, Luther took his vows seriously—maybe too

Luther read works by Saint Augustine and other

theologians. One idea stood out to him: that people could be saved through

faith alone. This idea of salvation by faith—rather than by doing good

deeds—helped him ease his own guilt and anxiety. It was also something he found

in the Bible, which made it even more important to him. This idea eventually

became a core part of his beliefs and actions later during the Reformation.

Martin Luther really thought deeply about these issues. He was educated and committed to his beliefs, and his thinking came from the humanistic tradition that had been developing since the 1300s in places like Florence and Rome. This tradition focused on critical thinking, and Luther became one of the people who took it seriously. He read Erasmus, thought about salvation, and found the idea of salvation by faith—the belief that one could be saved through belief in God rather than by doing good works—especially important.

This all came together for him when he saw what he believed

to be corruption within the Catholic Church. Around that time, there was a

Dominican friar named Johann Tetzel who worked with Pope Leo X, a member of the

Medici family. Pope Leo had spent a lot of money and was looking for ways to

refill the papal treasury. So, they increased the sale of indulgences—documents

people could buy that supposedly reduced their time in purgatory. These

were sold widely, and salesmen were sent out to promote them.

Luther reacted by writing a list of 95 points of concern—what

we call his 95 Theses. He didn’t actually nail them to a church door in

Wittenberg, as many people believe. Instead, he sent a letter to the pope and

to Tetzel, calling out what he saw as abuse and overreach in the church. He

mostly focused on the sale of indulgences and didn’t even go into papal

infallibility at first.

Tetzel and other church leaders were furious. They accused

Luther of heresy and summoned him to defend his ideas. This led to a formal

meeting called the Diet of Worms in 1521. The term diet here

means a council or formal assembly, and Worms is a city in present-day Germany.

This meeting was part of the Holy Roman Empire’s way of handling political and

religious debates.

Luther was promised safe conduct—meaning they guaranteed his

safety even if he was found guilty. He went, explained his views, and was asked

to recant, or take back, what he had written. At first, the focus was on

indulgences, but the discussion shifted to the idea of papal infallibility.

According to historian Andrew Fix of Lafayette University, the church pressed

After the meeting, Luther had 48 hours to leave town. His

refusal to back down from his beliefs, especially his rejection of papal

infallibility, marked a key moment in the conflict between reformers and church

authorities.

After Martin Luther was found guilty of heresy, he was

excommunicated by the Catholic Church. But one of the local nobles helped him

escape and hid him for a while. Word of what Luther had done spread quickly,

and many people supported him. Luther probably never intended to spark a

large-scale rebellion, but that’s what happened. A lot of people, especially in

the northern parts of Europe like Germany and the Netherlands, were frustrated

with the Catholic Church—not just over indulgences, but also over taxes and

other ways the Church had control over their lives. People didn’t want to keep

sending money to Rome or have Italian Church leaders influencing their

governments.

Luther ended up becoming a kind of symbol for resistance against Church control, even if he didn’t plan for that to happen.

This whole movement also affected art. For example, Lucas

Cranach, a German artist who supported Luther’s ideas, made prints that were

basically visual arguments for Reformation beliefs. One of his woodcuts uses a

scene from Matthew, chapter 21, where Jesus enters the temple and throws

out the merchants and money changers. According to the story, Jesus said, “My

house shall be a house of prayer, but you are making it a den of thieves.” This

was about stopping people from doing business inside a sacred space on the

Sabbath, which was against Jewish law.

In Cranach’s woodcut, that story is updated. On the left

panel, Jesus is shown in 1500s-style clothing, throwing out merchants dressed

like German businessmen. The apostles are behind him. On the right panel, it

shows the pope seated with a table in front of him, counting money and

indulgences. The top of that panel is labeled A. Christie, short for Antichristus—meaning

Antichrist. The idea here is that while Jesus acted to clean up religion, the

pope was doing the opposite, focused on wealth. It’s set up as a diptych,

or two-panel image, showing this contrast.

This kind of visual propaganda wasn’t limited to art.

Pamphlets and broadsheets—single printed pages meant for wide

distribution—were used to share Reformation ideas. By the 1540s, Martin

Luther’s writings were published all over the Holy Roman Empire. One broadsheet

published in Wittenberg was titled “Roman Devil” (Der Römer Teufel) and

used bold imagery. It showed a Hellmouth, a popular image in medieval

art, which was thought to be the entrance to Hell where the damned would be

dragged during the Last Judgment.

This print ties into some of the ideas that were already

being developed earlier in art and literature, like what we saw with Giotto

in the 1300s. That work was still very much Catholic. Over time, ideas about

the pope’s role began to shift, especially through the writing of figures like Dante

and eventually Martin Luther, who believed the role of the pope had become

corrupt.

In terms of art, the rise of printmaking really

changed the game, especially in the north. Albrecht Dürer, a German artist, was

the son of a goldsmith and trained in various techniques, including

printmaking. He also traveled to Italy and was exposed to Renaissance ideas. As

the Protestant Reformation spread, and the Catholic Church lost influence in

parts of northern

Dürer found one way around that by making prints and selling

subscriptions. It worked a lot like a magazine: you could subscribe and receive

a series of printed images. Prints were cheaper than paintings and could be

made in multiples, which let him reach more people and possibly even earn more

money. Instead of making one painting for one buyer, he could make hundreds of

copies and sell them individually.

But these prints also needed to line up with the beliefs of

his audience. In Protestant areas, religious art was only acceptable if it

clearly supported Christian teachings. Art couldn’t just be decorative or

secular anymore. It had to be focused on religious instruction or moral ideas.

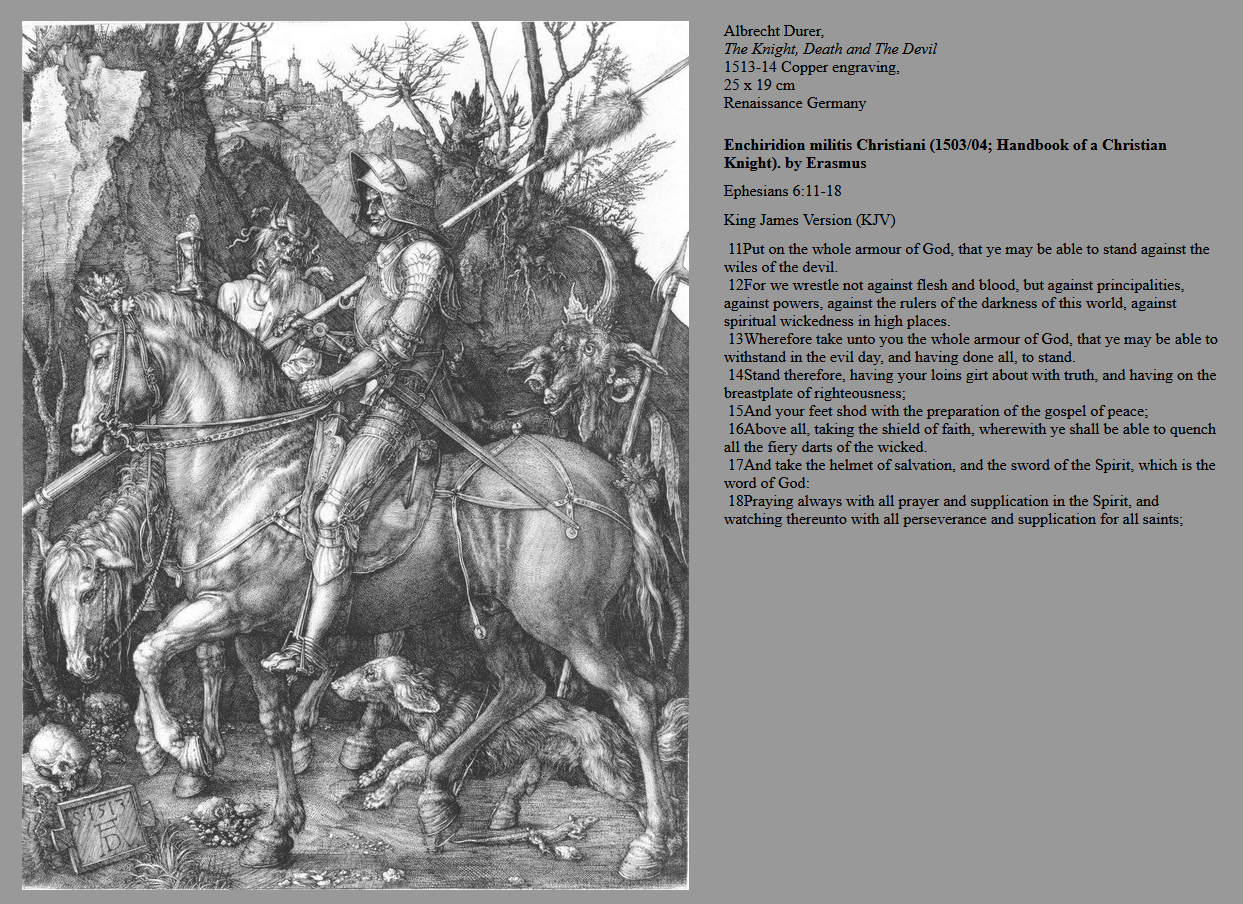

One of Dürer’s best-known prints from this period is called Knight, Death, and the Devil. While not directly quoting anyone, this piece lines up with the idea from Erasmus’s Handbook of the Christian Knight. That book talks about the idea that a Christian should be spiritually strong—like a knight—protected by faith the way a knight is protected by armor.

In the image, there’s a knight riding forward. Up in the

background is a castle, which might be a symbolic reference to the City of

God—a spiritual goal in Christian theology. The knight himself seems calm

and focused. Right beside him is a skeletal figure holding an hourglass—this is

a reference to memento mori, a Latin phrase meaning “remember that you

will die.” Behind him is a creature representing the devil. The devil looks

like he’s following, trying to distract or challenge the knight.

At the knight’s feet is a small dog, which could be a symbol

of loyalty or faithfulness. There’s also a lizard or salamander near the

ground, which might be meant to represent temptation or evil. At the very

bottom is a skull, another memento mori symbol, reminding the viewer of

mortality.

There’s also a little signature plaque worked into the image.

It says 1513 and includes Dürer’s monogram—“AD”—which acted like his logo. The

whole print was made with copperplate engraving, a technique that allowed for

really fine detail and multiple reproductions. These prints would have been

sold to individuals, especially those who supported the ideas of Martin Luther

or were part of the Protestant movement.

Imagine having a print like Knight, Death, and the Devil

in your home. If you were raising a kid and wanted to teach them to be a good

Christian, you might pull out this image and use it to explain how to resist

temptation, how to stay faithful, and what it means to live a moral life. These

prints were copper engravings, and they were detailed and reusable. Later,

we’ll look at how copper engraving differs from woodcut and intaglio

printing.

Come and study with me, videos, etexts, and study guides,

No comments:

Post a Comment