I'm having a Sale in my Etsy Shop 25% off of all original artwork.

Monday

I'm having a Sale in my Etsy Shop 25% off of all original artwork.

Friday

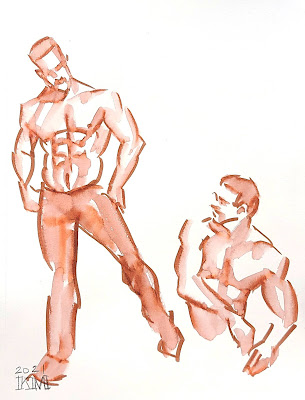

Ideas about watercolor.

What I paint is just as important as how I paint it. I try to choose subjects that don’t often get painted as part of mainstream culture. I try to focus on people of color and also homoerotic and non-binary themes and a special group of our friends the bears. It seems to me that you and I share in loving this subject matter of our art. I think that’s may be why you and I have connected as friends.

Part of what I’m trying to do is also paint them in an interesting way by focusing on things like composition, texture and color.

I want my compositions to be interesting and asymmetrical. So many figure paintings put the figure and the head directly in the center of the picture plane. I’m trying to put to focus points in more interesting places.

Watercolors always been a favorite of mine and one of the things that I like about working on paper and with watercolor is the freedom to experiment with monochromatic themes and with gestural marks. I’m not as frightened of making a mistake if the work is on paper and I’m not investing a ton of money into the supplies. In a way almost all of the work that I do on paper is kind of experimental because of this.

Tuesday

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Monday

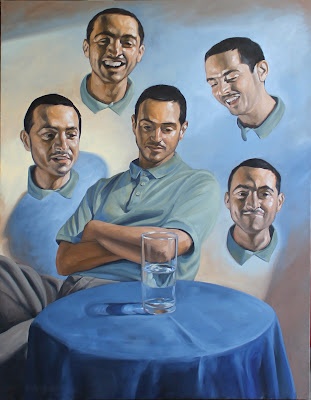

Vanitas, oil on canvas panel 11x14 inches by Kenney Mencher

I had a couple of things in my mind when I painted this.

I’m never sure how much art historical info my clients have so me just summarize that this is a “Vanitas” also called a “memento mori.” Basically, in Latin, one means he painting that deals with the vanity of human ego and life and the other term is literally a reminder or memento of death. I suppose because I had so many health problems in the last year and a half, I’ve become acutely aware of the aging process and how unimportant I am and also what my former ego tripping was about. I don’t want it to get too depressing about it but, I just sort of realized my place in the world in the last couple of years is not as grand as I had fantasized. So, the half jar or glass of water is a representation of the cliché having to do with “half-empty half-full” and the skull obviously of Hamlet’s soliloquy is a sort of reminder of where we all end up. It’s kind of a “point of view” painting.

Some of the ideas, granted are a little sad, but are about perspective and even the fact that I painted something outside of my normal subject matter is something that I’ve been discussing quite a lot in therapy with my shrink.

In terms of the formal or physical qualities, I’ve been really trying to keep thickening the paint and the paint texture and play more with color in my paintings. This is one of the few paintings that’s also painted directly from observation. I had actually set up a still life on a table next to my easel.

Saturday

Art School: Suggestions for Handling Group Critiques

While I was in art school and while I was teaching one of the more popular techniques employed by professors and teachers was something called the “group critique.” I’ve never liked them either as a student or as a professor and I actually think that “group crits” probably lead to more pretentious posturing, conflict and hurt feelings than any other behavior at art school. Here’s what they are and how to deal with them. (I’m also going to follow up with how to get give and get good criticism that’s useful.)

What is a “group critique.”

The group critique, aka group crit

in the classroom setting, usually consists of the students sitting in a circle

or roundtable while one student presents their work to the class.

The student is asked to present and explain their work to

the group and then the group is expected to provide thoughtful feedback. The presentation

is usually a 3-to-4-minute explanation using a lot of jargon or art speak to

explain what the goal of the work of art being presented was. After the

presentation, the other students in the class are invited to provide negative

and positive feedback about how successful the project was according to their

personal opinions. There are many variations on how this is conducted and in

general these kinds of presentations can lead to hurt feelings and alienation

as well as star worship and a popularity contest.

Part of the rationale for group critiques is for students to

learn how to speak effectively and communicate to an audience about their work

persuasively. Probably a better way to learn how to do this is to pay attention

in freshman English which teaches you a great writing format called the five-paragraph

essay. Also, take a creative writing course and write short

biographical stories about your experiences in the studio that you’ll be able

to use as artist statements and press pieces later. Go take a creative writing

class.

First of all, I think the most basic rule in any social

situation, classrooms, social media, a party, or even just hanging out with a

friend is to follow the adage, “if you don’t have anything nice to say, don’t

say anything at all.”

I understand that this sounds very simplistic but all one has to do is log into Facebook and see how much people love to take offense and argue in a social media setting to understand how unproductive and unconvincing arguing opposing points of view and just plain being nasty in a social setting can be.

My suggestion, for art school and social media interactions,

is to just be nice and try to avoid conflict where conflict is not necessary.

It’s always better to say nothing or to walk away from an argument rather than

to get into a feud with someone and have that become the precedent that will

govern the rest of your relationship with them. I’ve seen this happen time and

again in art school where jockeying for popularity and attempting to denigrate

someone or someone else’s work to make one feel better never works and in fact

can lead to long-term damage on a young artist's reputation.

When you’re in a “group crit” and you are the subject or

focus of criticism it’s best to respond by justifying or explaining why that

person is wrong in their judgment or criticism of your work.

Probably the best technique that I’ve seen when I’ve seen students confronted with overtly aggressive or negative criticism is for the person being criticized to just say,

“Thanks, I’ll think about that.”

“That’s great feedback, thank

you.”

“Thank you for your

observations, I’ll consider what you said.”

Or just saying, “thank you.”

And choosing not to reply beyond that.

This takes a lot of discipline because when one feels

insulted it’s a natural reaction to justify, argue or retaliate. Sometimes,

this also leads to attacks and negative divisive behavior even when the artist/student

who criticized you stands in the same spot and you choose to attack them, which

is equally a bad idea.

I’ve seen professors and teachers totally foster an

environment in which students are fighting for popularity and at each other’s

throats. The reasons why professors and teachers do this is often rooted in

their own treatment when they were in art school but sometimes, they just

rejoice in watching the drama and conflict unfold. Don’t fuel the sadistic

desires of people who enjoy conflict by participating in angry retaliation and

overt negative behavior. It won’t help you and it could hurt you in the long

run.

What do you do if you are expected to provide a critique in a group setting?

If it is possible and you are forced into saying something

say something positive about the student’s work such as complimenting one of

the formal aspects, line quality, color, composition, texture, perspective,

accuracy of drawing, or complement the content or iconography of the image.

You can say something nice about the content or the

meaning of the piece or say that it is a good fulfillment of the concept

that they had discussed.

Another possible compliment would be to discuss how

relevant the work of art is to the project, today’s world, a social issue.

However, sometimes professors will push students into conflict by insisting

that they say something about the work of art that needs to be improved or is

essentially a negative criticism. Here’s how to deal with that.

Again, it’s best to say as little as possible in a public

forum about someone else’s artwork, and to reserve any kind of criticism to a

private venue. Even if your professor is pushing for you to evaluate and

provide a negative comment about a fellow art students work it’s best to keep

it to a minimum and to keep it as factual as possible. For example, you could

use the elementary school teacher’s technique of the so-called “compliment

sandwich.” The complement sandwich consists of, compliment followed by a

palatable critique, followed by another compliment. Here’s an example,

“I like the composition in this

piece, perhaps the hand is a little too large proportionately, but I think the

content and meaning of your work is very powerful.”

Don’t go off on a long diatribe or a soliloquy about another person’s work of art because it just doesn’t feel good when someone does that and you’re up for critique in front of the classroom.

Why I’m against the use of the group critique in the

classroom.

I believe that the group critique is a sort of “Lord of the

Flies,” situation and always leads to people feeling slighted or having their

feelings hurt. At best it creates popular students who are clearly the rising

stars to follow at worst it creates scapegoats and victims in the classroom and

low self-esteem. It also creates an environment in which students learn how to

use buzzwords and phrases that essentially make them sound smart and in control

of the vocabulary but communicate even less.

I substituted group critiques with a much more labor-intensive

process in which I would write students individualized responses to their works

based on a rubric or criteria that I established before the project. Usually

when I was grading a work of art for student, I would provide several sentences

addressing the formal aspects of what they were learning, such as line, color,

composition, technique, texture, perspective, shading. I avoided using art

buzzwords or jargon. The second thing that I would provide would be an analysis

of the content or subject of their image and how effective it was in

communicating ideas. Again, I avoided a lot of heavy jargon however, I am

partial to the term “iconography.” Sometimes it was relevant, I would also

provide a sentence or two about how socially, politically, or emotionally

relevant the work was either to the student’s personal context or the world at

large.

So how do you get constructive criticism from other people while you’re in art school?

I have had a lot of good experiences getting constructive

criticism from professors, teachers, other art students, and friends by asking

them for it privately and also making sure that I ask only from people whose

art I respect and like. Sometimes

getting a private critique can feel much safer but can also hurt more because

this person is telling you something that you might need to hear. You have to

ask for criticism from people who have your best interest at heart and it takes

a lot of emotional intelligence to ask someone at to judge who really cares

about you and your development. Make sure it’s someone who makes good art.

Here are a couple of anecdotes about positive criticism

that I’ve received from artists who I respected.

John Stewart, University of Cincinnati 1993

While I was studying painting at the University of Cincinnati, I had a professor named John Stewart who made a comment in a life painting class to me about color theory and that he could help me with that.

John had already done a presentation of his art to our MFA

class complete with slides and biographical information. He also had just had a

show at an art gallery in downtown Cincinnati that I had attended and so I was

familiar with his landscapes and his art in general. I also was taking a life

painting class with and saw how kind he was to the other students and how he

conducted himself. I respected his work, his work ethic, how we communicate

with other students, and how he communicated with me when providing me with on-the-spot

criticism in the life painting class. This is someone I knew that I could

trust. I waited after class several classes and help to clean up and chatted

him up to see if he would be interested in starting a relationship with me.

|

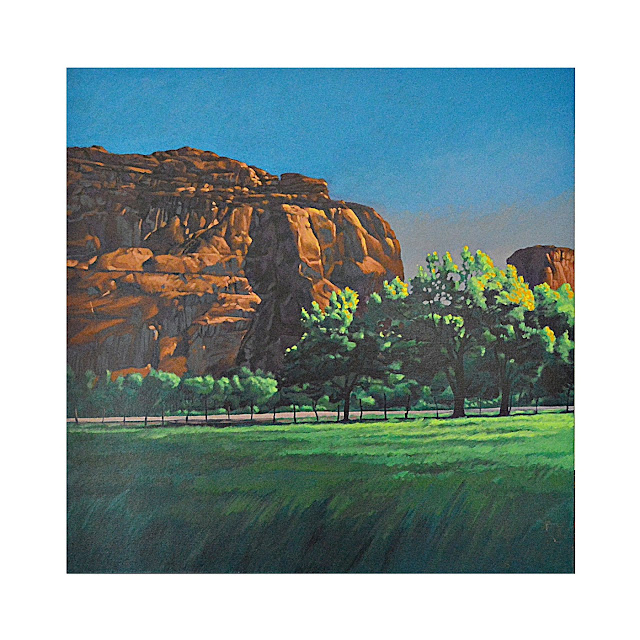

| John P. Stewart Oil on Canvas of a Canyonlands Landscape |

We arranged for him to come to my studio and John came in looked around, sat down, and took out a sketchbook that he used also as a notebook. He did not comment at all about the paintings on the walls or point out individual things in the paintings but instead started to talk to me about color theory and choices of pallets of color. He took some time and sketched out diagrams in his sketchbook to show me how color theory worked and then the next time I saw him he gave me a color chart and explained how I should use it. We would have biweekly meetings were he would come into my studio, often not looking at the work on the walls, but talk to me about things that he thought I need to know about color theory, suggested color combinations with oil paint, composition and anatomy. He also talked to me about how to behave professionally as well as introducing me to an art dealer who later on gave me a show. It was some of the most useful “criticism” I had ever received.

|

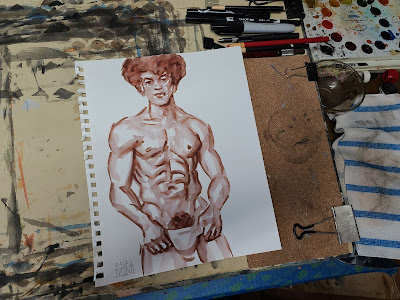

| Kenney Mencher, 45" × 35" mixed media on paper 2005 by David Tomb |

David Tomb San Francisco California

Another artist who I met 30 years ago while I was a graduate

student at Davis is an artist named David Tomb. David has looked at and

critiqued my work for at least 2 to 3 decades. I met him through a friend while

I was a graduate student studying art history at the University of California

Davis. I was a painter even though I was going through a two-year program for

an MA in art history. I visited his studio several times and even though I

really couldn’t afford it I bought one of his paintings and also attended

various shows he had in San Francisco. At the time that I was getting to know

him I didn’t really talk to him about the paintings I was making and never

asked him for criticism. He was just my friend whose work I thought was

phenomenal enough for me to buy.

Years later when I had already graduated from two masters’

programs and was teaching at Ohlone College in Fremont, David would invite me

to his studio to look at his work and we developed a relationship in which I

actually modeled for him for some drawings and paintings he was making. While

modeling for him we talked about art quite a bit and I picked his brains. After

a bit, I asked him if it would be all right if I were to bring by some

paintings for him to critique for me so that I could improve.

|

| Philippine Eagle, by David Tomb |

David’s critiques of my work were almost always overwhelmingly positive. However, that’s not to say that he didn’t make a lot of suggestions on how I could improve my paintings but he did it in such a seamless way using the “complement sandwich” that I talked about earlier in this essay. He would start by talking about how much he liked the content of the painting and in particular how much he liked my handling of the subject matter and what it meant to him. So, I was immediately put it ease and open to suggestions that he would make about the formal issues. His formal critiques of my paintings were thorough and very clear, and if it’s possible, very objective.

David would begin by talking about the edges of the figures

in the painting and where planes would meet. He would then go on to talk a

little bit about composition and paint texture. Sometimes he would address the

deficits in my anatomy, such as hands and the structure of the figures and make

suggestions as to where I might improve them. He rarely discussed color. Often,

he would talk about shading or chiaroscuro in the paintings often more in a

positive light.

What I’m suggesting in this story is that, first I respected

his work and even held him as kind of a hero for me as an artist. Second, he

was always kind and a kind of gentlemen in how he approached my work and even

when giving negative criticism offered solutions as to how to fix the problem.

This created trust because it wasn’t about him telling me with a great artist

he was or telling me that I wasn’t good enough he focused on how I could

improve my art. Over the years David also attempted to introduce me to gallery

directors and movers and shakers in the art world. By the way, even though he

attempted to pull me into his world which is a slightly more upscale kind of art

world I never really participated in the art world that caliber or level.

Something I’m actually not bitter about. In my mind David is just a different

kind of artist than I am.

__________________________________________________________

Afterword/Conclusion/Reaction

A bit of an ironic response happened after I shared this to a group that I administrate on Facebook. For me it is almost a perfect example of the ideas presented in this blog post.

Friday

Choosing an Art School or a College for Artists

I quit teaching at a community college in 2016 to become a full-time artist. (I was a tenured professor with 17 years at the college.) Since then, it’s been a pretty good experience and I’ve actually been making a very good living doing it and sometimes I wonder how I got here. One of the things that I keep doing now that I’m in my late 50s is thinking about decisions I made when I was a young person and what things I did right and what things I did wrong and what I wish that I could go back in time and tell my 18-year-old self. This is the advice that I would give myself when I was choosing to start as a college student.

Should Art Students Go to a School Entirely Devoted to

Art Practice? (I don’t think so.)

My advice to my past 18-year-old self would be to avoid

going to art school and instead go to a liberal arts college and major in art

history or another liberal arts discipline such as history or even economics

and study painting and drawing at a private atelier, such as those given by

artists, or schools such as the Art Students League in New York or schools that

teach painting techniques that I would want to learn.

Why Should You Avoid Art Schools?

Debt and expense. Art schools are a bad investment. They are

super expensive and often the outcome isn’t better for creating successful

artists that other schools.

The focus for most fine and performing art programs that I’ve attended and taught in is the creation of more academic (teachers and professors) rather than artists.

They are unfocussed and designed to give you a breadth of experiences rather than a focus on a particular style or technique.

The undergraduate experience for studying studio art at most colleges is very flawed, is designed with a one size fits all kind of philosophy, and in general doesn’t focus enough on one particular technique or ideology for most students because undergraduates who art majors are expected to study with a wide variety of professors with a wide variety of approaches to making art. However, if you look at the careers of these professors as artists, I think that most of them couldn’t make a living as an artist and rely on a tenured teaching position in order to continue to be able to make art. Also, if you look at the exhibition records of most of these professors who are at our colleges and art schools, it may put some doubt in your mind about how successful they are as an artist. (I think this may be true even for creative writing programs and performing arts.)

But I still want to got to an Art School. How do I choose?

You have to do real research and not depend on the catalogs

and information the school send you.

If you do want to go to college and go to an art focused

institution such as the Rhode Island school of Design or, the School of Visual

Arts in New York, the Pratt Institute or Savannah College of Art and design

etc. there’s probably a better criterion for picking a school rather than the school’s

overall reputation and/or the location of the school. The measure or criterium

that I would suggest is to specifically research the professors who teach in

the programs are interested in and find out if you are aligned with the kind of

art they make, and their level of success in the art world rather than in the

academic world.

Can you find students who attribute their success to a particular instructor?

What do the professors do his art professionals outside of

school?

Do these professors make good art?

I’m suggesting that art students look at the people they are going to go study with and see if that teacher is worth the extra tuition of going to that particular institution. You have to decide if you like that professor’s artwork if that professor is respected in the art world and you should also read reviews of the professors teaching and contact some of those professors’ former students to see if those professors have helped those students in any significant way.

Another way of researching or deciding what would be a good college for you to attend is to look at who graduated from that college and where they are now in terms of their professional arts career. For example, some of the more successful painters such as Kehinde Wiley, David Hockney, John Curran, Jordan Casteel, all went to really good art colleges and made the most out of the experience especially socially. They connected with the right people and also with the right professors and art professionals and made the most out of the experience of going to art school especially at a prestigious institution. If you were to look into an artist that you think is very successful and check out their resume you may find clues as to how you could follow in those artists’ footsteps.

Anecdotal Evidence Based on My Career

Here some anecdotal information about myself in my

experience as an undergrad and my experiences going to colleges.

Probably the most significant art education and training that I got as a young person was my experience going to the High School of Art and Design. In high school I had an excellent painting instructor named Irwin Greenberg. Greenberg ran an early morning painting class that was voluntary in which he showed us oil and watercolor techniques and allowed us studio time to work from live models. He also ran some illustration classes during the school day where he taught the same techniques. My career most closely mirrors his career.

Greenberg taught during the day and had studio sales and sometimes gallery shows of his art and made a good income by being a teacher and supplementing that income by having a private studio and painting as much as he possibly could in the hours work, he wasn’t teaching. Greenberg was born teacher and so he continued to teach at the school of visual arts in New York and I think he might’ve also given private lessons but through all of that time he painted as much as he possibly could and sold semiprivate leaf through studio sales and occasionally through galleries. A close associate of his who is also a teacher at Art and Design High School was Max Ginsberg who left teaching in the early 80s to pursue painting full-time and has had a robust in full career doing that since then.

My college experiences were not as good. I went to the University of Cincinnati as a studio arts major. I studied there for about a year and a half and most of the teachers I had were graduate students going for their MFA there.

I had a couple of full-time professors who exhibited in frequently and didn’t have much of a reputation nor career as a professional artist. Interestingly enough, the two most influential teachers I had Joe Norman and Daniel Ludwig both went on to become professors at other colleges and have robust careers as artists as well. However, I feel like I really learned the most in my basic drawing class and the rest of my experiences at the University of Cincinnati really didn’t train me very well to become a painter but, the art history courses and general and courses I took were so mind expanding that when I transferred to go to the City University of New York, Lehman College, in the Bronx I changed my major to Art History with a minor in the Honors Program. I took an occasional studio class but found them almost useless. Instead, I have a lot more success learning how to paint and draw by getting books out of the library that were how-to books as well as watching art videos and studying art history. Throughout my undergrad experience I continued to paint independently in a realist style basing my technique in the techniques that I had learned from Irwin Greenberg in high school.

Throughout my entire undergrad experience, I had only one studio teacher (Joe Norman) train me significantly in drawing and painting. Almost none of my studio instructors take a significant interest in my development as an artist nor did any of them do me any favors by introducing me to art professionals that they knew. Teachers and professors simply did not want to help and were often strangely destructive.

This is a theme that seems to be pretty consistent with many of the professors and teachers that I’ve encountered throughout the years both as a student and a teacher. The jealousy and the behind-the-scenes backstabbing are incredible. I had similar experience in graduate school. Professional jealousy, apathy, and self-interest interfered with most professors’ help to most of the students and I heard hundreds of horror stories in which professors refuse to help or literally sabotaged their protégés.

This essay is the expression of someone who is a bit of a malcontent and is certainly bitter after looking back at 35 years of an academic’s career. You should do your own research because there are stories about successful artists who had great experiences both in undergrad and graduate schools.

You will find that many of that attribute their success to a key educator who introduce them to a gallery or two and impresario or gallerist who helped make their career. If you look at the careers of David Hockney, Lucian Freud, Francis Bacon, and others you will see that there are two kinds of stories and experiences in which either an artist, a colleague, or a teacher did something that literally made that artists career. It’s just that this is the exception to the rule and not the rule itself. So, if you’re planning on going to a four-year undergraduate experience, specifically at an art college which will be very expensive, do your research. Find out as much as you can about the professors who teach there. Find out as much as you can about success stories and students who have come out and made a name for themselves and see who they studied with and try to reproduce their experiences.

My thesis, or main idea, is probably one that most people reject out of hand which is, I don’t think that it will really help your career to go to a specifically art-oriented college to become an artist. What I would suggest instead for most people who want to become an artist after they leave college is for them to go to a liberal arts college and major in subjects such as art history, history, humanities, business in general the liberal arts and for the same students to minor in studio art. If you’re really interested in becoming an artist and getting trained probably the best experiences you will have would be to study with an individual artist or at a supplemental art atelier.